Heirloom Bean VarietiesLearn all there is to know about planting, harvesting and saving heirloom bean seeds as well as the history behind some of the rarest and oldest heirloom beans. |

February 15, 2013

By William Woys Weaver

Heirloom Vegetable Gardening by William Woys Weaver is the culmination of some thirty years of first-hand knowledge of growing, tasting and cooking with heirloom vegetables. A staunch supporter of organic gardening techniques, Will Weaver has grown every one of the featured 280 varieties of vegetables, and he walks the novice gardener through the basics of planting, growing and seed saving. Sprinkled throughout the gardening advice in his book are old-fashioned recipes — such as Parsnip Cake, Artichoke Pie and Pepper Wine — that highlight the flavor of these vegetables. The following excerpt on heirloom bean varieties was taken from chapter 7, “Beans, Lima Beans, and Runner Beans.”

Buy the brand new e-book of Weaver’s gardening classic in the MOTHER EARTH NEWS store: Heirloom Vegetable Gardening.

To locate mail order companies that carry these heirloom bean varieties, use our Custom Seed and Plant Finder. Check out our collection of articles on growing and harvesting heirloom vegetables in Gardening With Heirloom Vegetables.

Heirloom Bean Varieties: Beans, Lima Beans and Runner Beans

‘Blue Coco’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

Also known in this country as Purple Pod and Blue Podded Pole, the Blue Coco bean is one of the oldest of the purple-podded pole bean varieties still under cultivation. It was known in France as early as 1775, and throughout the latter part of the eighteenth century it proved quite popular with American gardeners. By itself it is quite distinctive, and was shown attractively displayed in the Album Vilmorin (1870, 21). But when grown side by side with other purple-podded varieties, it is easily confused with them because many of the differences are slight. In any case, the other varieties are thought to have evolved out of Blue Coco. Therefore is it unwise to grow Blue Coco in the same garden with other purple-podded beans, since crossing may go undetected. In particular, do not grow it in the vicinity of the Lucas Bean, which it closely resembles.

Blue Coco has the advantage of hardiness and productive vines a good 8 to 9 feet in length. It is short season (about 60 days), more resistant to bean beetles than green-podded varieties, and survives dry weather better than many pole beans. It is also ornamental due to its rose-pink flowers, leaves tinged with purple, and of course its long purple-blue pods. The beans are harvested young as snap beans; their color disappears during cooking. The mature pods are thick and rather flat, and normally measure from 6 to 8 inches long. The ripe seed is chocolate colored, although the brown will vary due to soil and latitude. The dry bean can also be used in cookery. It has a rich, meaty texture.

‘Brown Lazy Wife’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

Not a true Lazy Wife, this pole bean is the P. vulgaris badius S. of von Martens (1869, 29). It was known in southern Germany and among the Pennsylvania Dutch as the Linsenbohne, or lentil bean, since it resembles a brown lentil in shape and color. In fact, the color is normally described as chestnut. It was used as a soup bean throughout the poorer agricultural regions of Germany, Switzerland, and northern Italy. In this country, it was commonly grown in the hill regions of western Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, and Ohio, the region from which it may originate.

The true origin of the bean is unknown, but it is believed to have been taken from Pennsylvania to Switzerland about 1705 by David Bondeli, a land agent who helped organize the 1710 Swiss Mennonite emigration to America. From Switzerland, the bean spread throughout the alpine regions of Europe. In colonial Pennsylvania the bean was sometimes used in conjunction with chinquapin flour to make dumplings, flat hearth beads, and soups. It was also combined with lentils and was one of the beans used in the vegetarian dishes of Ephrata Cloister during the early part of the eighteenth century.

The flower of the bean opens pale yellow, then fades to white. The vines are about 8 feet long and produce curved pods 3 to 4 inches in length. The dry bean ripens in 80 to 90 days. The vines will tolerate some shade and therefore can be grown on corn. Today, the bean is raised as a snap bean, but it is best as a dry bean, for it has a rich, lentil-like flavor.

‘Beurre de Rocquencourt’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

There are not many bush beans that can be described as elegant, but this French heirloom bean certainly qualifies. It was developed out of the old black-seeded Algerian Butter Bean, once so popular in early nineteenth century France. When the plant is full of golden yellow pods, it is truly an ornament to the kitchen garden. It forms a compact bush about 1 1/2 feet tall laden with 6-inch-long narrow beans. Each pod produces 7 black seeds. The pods ripen in 55 to 60 days but may be harvested much younger. A mature plant, with the leaves stripped away to expose the beans, is shown in the photo with the Blue Coco Bean above.

‘Caseknife’ Bean ![]()

Phaseolus vulgaris

Developed in Italy during the seventeenth century, this bean is one of the oldest documented pole beans cultivated in American kitchen gardens. Its name refers to the broad, slightly curving table knives once in use in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It has a similar commercial name, Schwertbohne, in Germany, literally meaning “sword bean.” Yet the bean also went by a number of vernacular names, the most common in this country being the Clapboard Bean. It appeared under this name in Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery (1796, 14).

The oldest strain of caseknife is white-seeded, although many subvarieties were developed in the nineteenth century. One of the leading French varieties was the Soissons, introduced into this country in 1841, according to the Magazine of Horticulture (Hovey 1841, 134–39). There is also an old brown-seeded variety still in circulation in this country. However, the white-seeded sort is the one cultivated by Thomas Jefferson and the subject of this discussion. It was considered the best of its type by most early American horticulturists.

The vines are robust growers, reaching 8 to 9 feet, one of the characteristics of the old, original strain. The flower is white fading to yellow, yielding long, flat pods 8 to 9 inches in length with white kidney-shaped seeds. The pods make excellent snap beans when harvested about 5 inches long and a quarter-inch wide, although historically, 6 1/2 inches was considered the proper stage, especially for drying the beans or for shredding them for pickles. At 5 inches, the pods have a rich flavor similar to butternuts and do not require stringing. The dry beans, useful in winter cookery, mature in about 75 to 80 days, the snap beans in about 60.

Historically, there were a number of dwarf or bush versions of this bean, particularly in Germany and Italy. One of the German varieties cultivated today is Pfälzer Juni (Palatine June), a bean that is forced, then planted outside and brought to market in mid-June with little bundles of summer savory. Another Palatine bean, and probably the closest surviving variety to the original caseknife beans of the 1600s, is the Pelzer Schwertebuhne (Palatine Caseknife Pole Bean) preserved by the Wendel family of Weilerbach in the Rheinland-Pfalz. I offer the Wendel heirloom through Seed Savers Exchange under its old Palatine name.

‘Egg’ Bean or ‘All-in-One’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

In the German Rhineland there are several variant forms of this bush bean with egg-shaped seeds, most of which are mentioned by C. A. Fingerhuth in his 1835 study of the agricultural botany of the lower Rhine. The pale-yellow-seeded variety was known in France as the haricot de Sainte Hélène, but most of the others were simply called Canada Beans (haricots du Canada). The light brown variety, which is the subject of this sketch, is known in this country by several aliases, including Dutch Caseknife and Fisher Bean. It is not a true caseknife type, but it is the same as the Eierbohn of von Martens (1869, 63) or more commonly, the Einbohn, or All-in-One Bean.

The origin of this bean is presumed to be eastern North America, for it was known in its original form at least to a number of Algonquian peoples. It is thought to have been related to the Turtle Bean of the Unami-speaking Delawares, but if so, the bean has undergone considerable improvement since its transplantation to Europe, since it no longer exhibits many of the “wild” qualities of true aboriginal beans.

The Egg Bean is a variety of bush bean about 15 inches tall and quite prolific. It was cultivated among the Pennsylvania Dutch and is now offered by the Landis Valley Heirloom Seed Project as the Fisher Bean, after the family that preserved it. The flower opens yellow, then turns pink. The green seeds are used as a shelly bean when very young, but on the whole, this variety is cultivated mostly as a dry bean for soups and winter dishes. The dry bean ripens in 90 to 100 days and is tan in color, with a maroon circle around the eye. It has an excellent meaty flavor and holds its shape well when baked. In fact all of the beans of this type were great favorites with the French for cassoulets and similar preparations.

The following recipe for an Anglo-Canadian version of the ubiquitous baked bean is taken from The Home Cook Book, published in Toronto in 1887.

Canadian Baked Beans Recipe

Boil the beans, until they begin to crack, with a pound or two of fat salt pork; put the beans in the baking-pan; score the pork across the top, and settle in the middle: add two tablespoons of sugar or molasses, and bake in a moderate oven for two hours; they should be very moist when first put into the oven, or they will grow too dry in baking, Do not forget the sweetening if you want Yankee baked beans.

‘Hickman Snap’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

The name of this popular pole bean refers to the Hickman family of Draper Valley, Virginia, from whom the beans were first obtained by seed savers. The history of the bean is otherwise obscure, although it is known that the Hickmans came down from Pennsylvania in the 1730s, so the bean may have originated somewhere else. But since the bean shares traits with the Old Virginia Brown Cornfield Bean, which is said to be of Cherokee origin, it is probably an amalgam of several varieties. It is certainly one of the few heirloom beans that produces many types of beans at once, a true sign of a recent cross.

The bean is circulated among seed savers as a snap bean, for which purpose it is excellent. However, this is one of the finest dry beans of all the heirlooms now in circulation and much overlooked for this quality. The beans themselves probably contribute an interesting balance of flavors because they are a curious mix of colors and variant shapes. The colors include dark slate gray, chocolate brown, honey tan, black, and a gray white, but not all in the same pod. There are also several pod types, the largest measuring 7 1/2inches long with 9 beans per pod, another measuring 6 1/2 inches long and quite narrow. Others fall between these extremes. The dry bean may be harvested in 90 days.

Some gardeners have reported that after they have grown this bean for several years, it degenerates into two bean types, one with slate gray seeds, the other with taffy brown seeds. I have also observed this, but it has not in any way compromised the quality of the dry bean when cooked. The secret to its excellent flavor, which resembles country smoked bacon when properly prepared, is sea salt used liberally.

‘Ice’ Bean or ‘Crystal White Wax’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

Nineteenth-century German authority on beans Georg von Martens claimed that while Dutch plant breeders had hybridized the Ice Bean, turning it into one of the most intensely bred of all bush beans, it was the English who first developed it as a forcing bean for hothouses. The French, who once used the bean extensively as a garnish in high-style food presentations, lumped it together with similar sorts under the generic name haricot princesse. Italian horticulturist Achille Bruni reported that several forms of this bean existed in southern Italy long before 1845; thus we are dealing with a bean of considerable horticultural interest and a convoluted genealogy.

The bean is not well known today, at least among American gardeners, probably because we were never much for cultivating beans in greenhouses. Since the bean was created for forcing, it does not always thrive in the open ground. Its pods are tough if raised outdoors in arid climates, or when they not harvested at exactly the right moment. Yet the harvests are epicurean if properly attended to, and the dainty little beans a blueblood’s feast when gently poached in white wine and brought to the table in picturesque bundles tied with chives. They are visual treats because the pods are miniature, with a cool, silvery green color that looks misted or frosted — hence the bean’s name. The pods retain this coloration after cooking, especially if they are steamed.

The bushes are small, with the pods close to the ground. In a greenhouse, they would be low for easier picking.

However, in spite of its highly inbred character, the variety retains some very old traits, among them runners often 3 feet in length. To keep the pods off the ground, it is advisable to support each plant with a small bamboo stake. Let the runners tangle themselves around that rather than one another. Allow 45 to 60 days from planting to harvest, but plant in succession for a continuous crop until frost. The pods are 3 to 3 1/2 inches long and at their best for harvesting for only a day. The plants must be checked every morning. Once the tenderness has left the pods, the beans can be picked for shelly beans. Nineteenth-century seedsman James Vick of Rochester, New York, recommended the Ice Bean exclusively as a shelly bean, and I do agree with him that it makes a delicious faux petit pois with a rich, nutty flavor. However, the dry bean is also quite useful, for it is small and white and can be cooked like barley. When the pods ripen on this variety, they begin to turn purple, a true mark that this is the correct strain of ice bean.

There are many other beans circulating under this name. One of them, the White Ice Bunch Bean, is not synonymous. Its pods ripen yellow, but otherwise the bean may be used like the Ice Bean of this sketch. In the Midwest, a bean circulated among the Germans in the nineteenth century with the name Speckbohne, has recently come into circulation among seed savers from a source in Klemme, Iowa. This bean is indistinguishable from the true Ice Bean. The small beans of the Ice Bean were also used to make an excellent soup like the one given below from Lettice Bryan’s Kentucky Housewife (1839, 21). What she actually proposes in her recipe is a soup made with bean-and-rice dumplings. By “liquor,” she means soup stock.

Dried Bean Soup Recipe

Take the small white beans, which are nicest for this purpose, hull them, and parboil them in clear water till they begin to swell. Then rinse them in clean water, and boil them very tender, with a piece of salt pork; then take out the pork and beans; mash the beans to a pulp, and season it lightly with pepper; mix with it an equal portion of boiled rice, which has also been mashed fine; make it into small balls or cakes; put over the yolk of egg, slightly beaten, dust them with flour, and spread them out on a cloth to dry a little. Having seasoned the liquor with salt and pepper to your taste, put in a large lump of butter, rolled in flour, boil it up, stir in half a pint of sweet cream, and then put in the cakes or balls. Serve it up immediately, or they will dissolve, and make the soup too thick. This is a plain, inexpensive soup, but a very good one.

‘Indiana Wild Goose’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

A bean of unknown origin but with extraordinary culinary merits, Indiana Wild Goose deserves better recognition. It is a vigorous pole bean with 8-foot vines and good resistance to drought. The flower is yellow fading to white, producing large, flat pods 5 to 6 inches long and 3/4 inch wide. There are normally 6 beans per pod. When the beans reach the shelly stage, the pods acquire a handsome rose-pink blush. The dry seed may be harvested in 100 days. At first, the ripe bean is flesh colored, then it turns to khaki. The vines are highly productive, and the bean has a rich, nutty flavor. Best of all, the bean seems to do well in most parts of the country, for I have received good reports from members of Seed Savers Exchange in Washington State, California, Georgia, Ohio, and New Hampshire.

‘Lazy Wife’ (Hoffer’s Lazy Wife) Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

The Lazy Wife of America kitchen gardens is not the original German bean of the same name once popular throughout southwest Germany, Alsace, and Switzerland. That bean, known as the “True Lazy Wife of Swabia,” is a scarlet red, pellet-shaped bean identified by Georg von Martens (1869, 72) as P. sphaericus purpureus M. He had this to say about it: “In Stuttgart, I found these beans for sale not only from all the commercial garden suppliers as Purple Cardinal Pole Beans, Stringless Cardinal Beans, and Early Imperial Snap Beans, but also they were called by common gardeners Lazy Wife Beans (Faule-Weiber-Bohnen) because one need not string them before cooking.” It was this stringless feature that earned the bean its colorful name. The Swabian bean and the Pennsylvania Dutch bean share only one similarity: they are both Kugelbohnen, a type of bean Germans likened to grapeshot owing to its shape and size. Otherwise, the bean we call Lazy Wife, and which the Pennsylvania Dutch call Fault Fraa Buhne, is an altogether different variety. For one thing, the bean is white.

The Faule Fraa of Pennsylvania was introduced into this country in the latter part of the eighteenth century under its standard German name Sophie-Bobnen (Sophia Bean), the Phaseolus sphaericus albus of von Martens and the White Cranberry discussed in the Gardener’s Chronicle (1842, 236). Actually, these last two beans are slightly different, but they were generally treated as the same variety and often allowed to mix. The Philadelphia seed firm of William Henry Maule asserted in the 1890s that the bean originated in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Maule’s bean may have been a Bucks County selection, but the bean had been sold to local farmers as early as 1802 by Bernard M’Mahon under the name Round White Running. It was also known as the San Domingo bean. It would appear that Maule simply rediscovered a common old German variety and created a new name for it.

The bean is a vigorous climber and can withstand some shade, which makes it ideal for growing on corn. The vines are 4M to 5 feet tall, with abundant foliage. The flowers are white, the pods glossy green, about 5 1/2 to 6 inches long. There are normally 5 to 7 seeds per pod. The pod is flat, slightly curved, and when the seeds are fully formed, bulged and bumpy. The beans are ivory white.

The pods are considered excellent for snap beans, but as a shelly bean, this variety is unequaled by any other. The dry bean is an excellent soup bean. The Pennsylvania Dutch normally puree it when cooking it in soups.

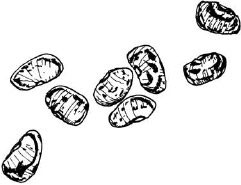

‘Light Brown Zebra’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

The “zebra” bean is a pinto bean recognized by Georg von Martens as a distinctive bean type notable for the dark zebra stripes running lengthwise down the sides of the beans. Some zebra beans familiar to Americans include Oregon Giant and its Swiss counterpart Weinländerin (Maid of the Wine Country), Scotia, and Tennessee Wonder. The origin of this group of beans, which includes a wide range of shapes and colors, is probably Mexico or the American Southwest. However, the beans were dispersed at such an early date that is now difficult to sort out their tangled history. One of the most colorful to my mind is the zebra bean called Rio Zape, a violet pole bean with maroon markings. It is recorded by von Martens as the Amathyst-farbige Zebrabohne (Amethyst Bean). In Spain this variety is known as judias de Largato. Less well documented is the Light Brown Zebra Bean of this sketch. As a patterned bean, it is striking; but most important, it is a prolific producer.

The bean is widely known among American seed savers by a variety of thoroughly incorrect and misleading names. It is often called Refugee Bean, which it is not. It has come to me as Thousand-for-One Bean, which, again, it is not. It has even been called an old Pennsylvania Dutch bean, even though the Pennsylvania Dutch do not have a name for it. But von Martens knew it, calling it Phaseolus zebra spadiceus S., and it is one of the best bush beans of its kind.

Italian botanist Gaetano Savi, who gave this bean its Latin name in 1822, described its color as nocciola (hazel), which I find poetic. The bean certainly deserves a better name than the one it has. In any case, it is a vigorous bush variety about 14 inches tall, producing rose-pink flowers.

The pods yield 5 to 6 seeds each; they are shown in the drawing with their distinctive zebra markings. The plants are extremely sensitive to weather conditions and will slow down or speed up their ripening to accommodate it. They are a good 60-day bean when all things are equal. I have harvested the beans in the early fall, leaving the bushes completely stripped of pods, only to have the plants revive during a warm spell and produce a second crop before frost. Perhaps it should be called the “fail-safe bean,” because for a beginning gardener, it is one heirloom that repays the effort ten times over.

The dry bean is the part used, and it can be incorporated into any recipe where Mexican pinto beans are called for. It also makes a delicious bean paste. And since a strain of this bean was discovered in Ethiopia in the early 1840s, it can also be used in East African recipes with perfect authenticity.

‘Low’s Champion’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

This popular New England bush bean was introduced in 1884 by the Aaron Low Seed Company of Boston. The American Garden (1889, 57) suggested that the bean was an entirely new variety created, as Low himself claimed, by crossing a wax bean with a “green bean.” Later field tests revealed that it was merely an old strain of the Dwarf Cranberry Bean under a new name. Its popularity, however, is still widespread, and for bean flavor, it has few peers both as a shelly bean and as a snap bean.

The plants grow about 12 to 15 inches tall, remaining very compact, and bear pods that hang down straight to touch the ground. The flowers are pale pink, yielding long, flat stringless pods about 4 1/2 to 6 inches long. There are normally 4 to 5 seeds per pod, oval in shape, and very dark red when ripe. The beans ripen in 70 days and are therefore considered one of the best for short-season areas, hence the immense popularity of this variety in New England.

‘Mostoller Wild Goose’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

The history of this bean, as related by one of the Mostoller family, appeared in the Somerset Democrat (Somerset, Pennsylvania) for December 9, 1925. It is one of those bean varieties that has become a metaphor for the heirloom seed movement; its story is well known and was reprinted in the 1984 Fall Harvest Edition (1984, 148–50) of Seed Savers Exchange. The family’s story about the bean connects it to Civil War veteran John W. Mostoller, who shot a wild goose with beans in its craw. The beans were planted in 1866 and then preserved by the family as an heirloom vegetable ever since. There is a possibility that this tale is indeed true, yet it is important to keep in mind that seed found in the craw of a goose is one of the most recurring themes in American horticultural literature, and is often folkloric.

The problem with the genealogy of the Mostoller Wild Goose bean is that while the legend is winning, the goose must have flown a long distance; there is a family of beans from northern Italy, the Porcelain Bean among them, to which our goose bean belongs. Furthermore, it is not a bean recognized by von Martens, which would suggest that the variety and all of its Italian relatives developed after 1870. This includes the Snowcap Bean, which is identical to the Mostoller bean, except for slightly different coloring—purples instead of browns.

No matter. The bean is excellent baked and is delicious in soups. The huge vines seem to thrive when allowed to clamber up giant sunflowers. Otherwise, it is a pole bean that would easily choke out corn. It should be raised for best results in teepees or on very tall stakes. This is because the vines can attain a height of 10 to 12 feet (6 to 10 feet, the normal description, is too conservative). The flower is white, producing pods of about 5 inches long and containing 4 to 5 seeds per pod, sometimes 6. The seed is very large, white on the underside and heavily speckled with brown and maroon over an orange patch around the eye. If nothing else, the bean is striking for its ornamental quality, which it loses once cooked.

‘Pea’ Bean or ‘Frost’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

The English make quite a fuss over pea beans. Jeremy Cherfas, former head of genetic resources at the Ryton Organic Gardens in England, wrote a short piece on pea beans for the garden’s newsletter in 1994 because there has been a resurgence of interest in this family of heirloom beans. It is evident that Americans and British gardeners use the term “pea bean” quite differently, even though we are both discussing beans with seed of the same general shape. In America, the term is applied to white, pea-like Marrowfat Beans, such as the Boston Navy Bean.

Our white pea beans originated with the Iroquoian peoples of New York State, and there are now well over a hundred distinct varietal forms, as well as many synonyms. All of the white pea beans are bush types. The pea bean of this sketch, however, is the two-color pole variety of England, known in this country as the Frost Bean, or Fall Bean. In Beans of New York (Hedrick 1931, 72) the bush form is called the Beautiful Bean, and is only present in the book as an illustration, for there is no discussion of it in the text.

Amelia Simmons called this bean the Frost Bean in her American Cookery (1796, 15), noting that she felt it was only fit for shelling. As a shelly bean, it is indeed fine; as a dry bean even better. This bean first came to me not as the Frost Bean but as the Gross Nanny Green Pole Bean (Der Grossnanni ihr orient Schtangebuhne) preserved by the Miller family near Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. The Millers use it as a snap bean, but it is excellent as a baked bean or boiled for bean salads.

The seed is white, with a large irregular splash of maroon around the eye. Georg von Martens (1869, 76) identified this pole bean as the Halbrotbe Kugelbohne (Half-Red Grapeshot Bean). The Miller bean blooms with a yellow flower fading to white; von Martens’s example had rose flowers. Evidently, there are two variant forms of this bean in terms of flower color; otherwise, the plants are the same. In Germany the young pods were eaten green in salads. In South Africa the same bean was known as the Zuiker Boon and served with sour-cream dressings. James J. H. Gregory introduced the bicolored pea bean in his 1875 catalog. It was considered quite new at that time. In England, however, it became one of the most popular of all dry pole beans, valued in particular for its meaty flavor and its reliability in northern latitudes with cool weather. In the American South, it is called the Fall Bean for this reason.

One year I planted a crop on July 1, and by September 1 it was producing heavily. For me, it has become a good late-season bean, since I can plant as late as August 1 for green beans in October and dry beans in November. I believe that the ability of this bean to produce so late in the season when evening temperatures are cool or even chilly is one reason it has earned the colloquial name Frost Bean.

The vines range from 8 to 9 feet in length, producing pods about 4 to 5 inches long. The bean is not tolerant of drought. If conditions are dry, the beans will become shriveled or sunken instead of plump.

‘Red Cutshort’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

This excellent bean has been ignored in horticultural literature; nonetheless it has existed in the South for many years. Beans of New York (Hedrick 1931) incorrectly assigns the name red cutshort to the Cornhill Bean, now known as the Amish Nuttle Bean. The two could never be confused, not even by children. The true Red Cutshort is nearly the same red color as the Red Cranberry Pole Bean, although a shade brighter (for gardening advice on the Amish Nuttle Bean and Red Cranberry Pole Bean varieties read Grow These Heirloom Bean Varieties). Its pod is similar to the Amish Nuttle Bean, vines the same length, and it also requires the same long growing season. As with all cutshorts, the seed is small—a feature I happen to like—and the pod production prolific. The bean can be used like a red mung bean in cookery, but Southerners have preferred to use it with rice and dried okra dishes, especially in the Deep South. Culturally, it served the southern farmer in the same manner as the Red Cranberry Bean in New England. Among the native peoples of the South, the bean was used for flour and cooked in combination with cornbreads or dumplings.

The vines are about 8 to 10 feet long, producing 5-inch pods with 6 to 8 small red seeds in 75 days. If the beans are harvested young as a snap bean—for which they are popular—the vines will produce all summer until frost. The vines can tolerate some shade and therefore can be cultivated on corn hills. Contrary to reports in the Beans of New York, Georg von Mattens was quite familiar with cutshort beans, which he called Eckbohnen (beans with “square corners”). Regarding the red cutshort of this sketch, which von Martens called Phaseolus gonospermus purpureus Martens or Purpurrothe Eckbohne, he recognized several subvarieties. It closely resembled a French variety sold in the 1860s by the Paris seed firm of Beaurieux under the name haricot rouge de Chartres. Not surprisingly, when von Martens tried to grow cutshorts, they would not come to crop for him any better than lima beans. Germany is simply too far north.

As an alternate experiment, in 1858 von Martens acquired a red cutshort bean from Russia sold by the seed firm of Rampon in Lyon under the name haricot de Russie, as well as another red cutshort from the Russian city of Aigur on the Amur River along the Manchurian border. This latter variety, which had evolved under northern conditions, brought forth a small crop of beans. But the experiment convinced von Martens that cutshorts are not only long-season beans, they do far better in southern latitudes where the night air is warm. I would take von Martens’s conclusions to heart. This is not a bean for Minnesota or Idaho.

‘Red Valentine’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

In 1889 the American Garden (1889, 57) remarked on the introduction of the Extra Early Red Speckled Valentine, calling it a “capital round bean.” Ever since valentine beans have come on the market in this country, they have been valued for their long, pencil-shaped round pods, the snap bean par excellence. And not surprisingly, since years earlier, the American Agriculturist (1870, 123) put the Early Red Valentine at the top of the list for American kitchen gardens. Over the years, the number of valentine types and subvarieties has proliferated to such a degree that the history of this bean has gotten lost in a tangle of commercial claims.

Fortunately, Georg von Martens was able to sort out its history when the individuals involved in the development of this variety were still living. In his bean book, he styled the bean Phaseolus oblongus turcicus, Savi, since Gaetano Savi had actually been the first botanist to catalog it. In German, the name was given as Türkische Dattelbohne (Turkish date-shaped bean) owing to the widespread presumption that it had been introduced into Europe from Turkey. Actually, Prince von Neuwied was the first to observe the bean among the Indians living along the Missouri River in 1815–17, and he noted its name in their language: ohmenik pusaebne (as written phonetically in German).

The bean was taken to Europe — by whom it is not determined, but certainly Prince von Neuwied would be a logical candidate — where it acquired the name Thousand-for-One Bean at the hands of Dutch plant breeders. In England, the bean was called the Refugee Bean or Purple-Speckled Valentine. In Germany, it was called Thousand-for-One, Little Princess, and Salad Snap Bean. It made its appearance in this country about 1837 at David Landreth’s seed farm near Bristol, Pennsylvania. From there, it was launched as a new bean, never mind the Missouri Indians. In any case, there is only one original Refugee Bean, original Thousand-for-One Bean, original Valentine Bean — and it is this one.

The bean produces a bush about 15 inches tall and, typical of the old sorts, throws out a runner some 2 feet in length. The flower is a rich rose pink; the 5 1/2-to-6 1/2-inch pods, long and narrow, are ideal for snap beans, the primary use of this variety. True to its name, the oblong seed is heavily speckled in deep wine red arranged in a zebralike pattern, with a flesh pink ground.

‘Scotia’ or ‘Genuine Cornfield’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

![]()

This old bean acquired its common names late in the nineteenth century, for it cannot be found in most horticultural works until its commercialization in the 1890s. Georg von Martens called it the phaseolus zebra carneus Martens, although it was only one of ten similar zebra beans listed by Savi in 1822. In the Veneto of northern Italy, the bean was known as fasioi tavarini. In fact, it could be found in most parts of Europe. Von Martens considered it one of the most beautiful of all the zebra beans and also the most common.

It seems strange that our records would be so silent on this bean when it is thought to have been indigenous. This assumption is doubtful, even though the bean was recorded among the Iroquois at the turn of this century as a bread-and-soup bean. In several Iroquois dialects the bean is even referred to as a “wampum bean,” one of the gift foods used for settling contracts and marriage dowries in Iroquois society. Just the same, the bean does not appear to have been among the Iroquois until after contact with whites, for the true source of the bean is Mexico. Thus, instead of calling this a cornfield bean, it would be more authentic to refer to the Scotia bean as frijoles de milpa, the name by which it was known when it entered Louisiana with Spanish occupation in the eighteenth century.

The obscure origin of the bean has always been outweighed by its productivity, for the bean is doubtless one of the best yielders of its type. The vines grow 14 to 15 feet long and produce 6-inch pods with 8 to 9 beans per pod. The beans are buff or flesh colored with brown zebra markings, although not as pronounced as on most other zebra types. This is a 90-day bean and a heavy cropper that grows well on corn. It can be harvested as a snap bean, but is best as a shelly bean or as a dry bean.

‘Sulphur’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

The name of this bush bean is in fact a catchall term for a number of similar beans that spring from a common source. Because they have crossed and recrossed over the years, very few of them now fit neatly into old horticultural descriptions. Fearing Burr recognized two varieties, the Golden Cranberry and the Canada Yellow. They are considered synonyms by Beans of New York (Hedrick 1931), but Canada Yellow comes closest to matching the Sulphur Bean of Seeds Blüm, the most authentic strain I have thus far encountered on the market today.

Georg von Martens referred to this bean as the Yellow Egg Bean, and it was known earlier to Italian botanist Gaetano Savi. The French referred to one of their yellow hybrids created from a yellow-and-white cross as the haricot petit Nanquin (Little Nankeen). This name referred to the resulting color, not to a place of origin. This hybrid, which was not yet stable when it was introduced in 1839, came to be known as China Yellow. The Sulphur Bean should not be confused with the bean called Early China, also known as China Red Eye. This last bean was well known in New England and was often mentioned by Thomas Fessenden in his agricultural works, including The Complete Farmer (1839, 154).

The Sulphur Bean is a bush variety about 16 inches tall that produces pink flowers. The pods are about 5 inches long and contain a dry seed ripening in about 95 days to a soft sulphur yellow. Around the eye of the bean is a small pink-brown ring. The ring around the eye of Golden Cranberry is green; otherwise the two beans are similar. Either one may be sold as the Sulphur Bean. I have even seen the two mixed in the same seed packets. The true Sulphur Bean, however, is the object of epicures, for it is famous as a stewing bean that cooks down to a creamy texture. It is extremely popular in the South as an ingredient in bean gravies, and when pureed, it makes an excellent base for soup.

‘Turtle Bean’ or ‘Turtle Soup’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

Prior to the war with Mexico (1846–48), the Turtle Bean was largely uncultivated in the United States except by a small circle of seedsmen and plant collectors. The only exception to this was Louisiana and other parts of the Gulf Coast where early contact with Mexico occurred. In those areas, the bean was also an important ingredient in the diet of slaves, hence its vernacular name pois à nègres in the French-speaking Caribbean. Along the hot Gulf Coast of Mexico, where the bean originated, it is known as frijoles de Tampico or simply as frijoles negros. Its counterpart from the cool Mexican highlands, also a black bush bean, is the Veracruzano that was introduced into the United States by soldiers returning from the Mexican War.

Georg von Martens (1869, 27) noted that several German seed houses had tried unsuccessfully during the 1840s to introduce the bean into that country as an alternative to the failed potato crop, but concluded that “for us it was too black and too small,” not to mention that the growing season in much of Germany was too short for it. Round, black, and ugly, this was a bean that Europeans could not cook with milk or cream. Indeed, anything cooked with it turned a dark inky color. Yet as von Martens, pointed out, the Turtle Bean was well known under many different names in many parts of the world because it had been widely disseminated by the Spanish during the 1600s. He recorded identical samples from Louisiana, Algeria, Brazil, Portugal, and Chile, and noted that Mexican settlers had introduced the bean into Texas well before 1815. From there it spread into many of the Indian tribes residing in the lower Great Plains.

Under the heading of “Valuable New Vegetables,” the Horticulturist (1848, 464) launched a campaign to introduce the bean to American gardeners under the enticing name of Turtle Soup Bean. The New York seed firm of Grant M. Thorburn & Company was most active in commercializing it, but other seedsmen also followed suit. Furthermore, the U.S. Patent Office distributed seed to farmers in several parts of the country. It is interesting that Back Turtle Bean the bean was not initially sold on its old merits as a dry bean, for resistance to black-colored food was very strong in that period. Rather, it was marketed as a snap or string bean, since the pods remained tender for a long time. Very few beans at the time could compete with it on that point.

History does not record the name of the creative cook who transformed these beans into ersatz turtle soup, but anyone with a little pepper wine on hand can easily see how it happened. In any case, the sherry transformed a mundane gray broth into an acceptable gentleman’s dish, whether or not it resembled real turtle. One of the earliest recipes for turtle bean soup was published in the Horticulturist, and the knowledge that it came from the hand of Alexander Jackson Downing (or more likely his wife) doubtless added to its glamour. But it was Henry Ward Beecher’s recipe that became the most famous and indeed the most popular with period cookbook authors. This was the same Henry Ward Beecher whose articles on gardening in the Western Farmer and Gardener were collected and republished in 1859 as the best-seller Plain and Pleasant Talk about Fruits, Flowers and Farming.

Jane Croly published his recipe in her Jennie June’s American Cookery Book (1874, 327). It needs little clarification other than a footnote to explain that a “bean digester” is a type of Victorian stewpan with a tight-fitting lid. It functioned along the same principle as a pressure cooker. Of course, being a minister, Beecher abjured the sherry.

Henry Ward Beecner’s Favorite Turtle Bean Soup Recipe

Soak one and a half pints of turtle beans in cold water overnight. In the mottling drain off the water, wash the beans in fresh water, and put into the soup digester with four quarts of good beef stock from which all the fat has been removed. Set it where it will boil steadily but slowly till dinner, or five hours at least — six is better. Two hours before dinner put in half a can of tomatoes or eight fresh ones and a large coffee cup of tomato catsup. One onion, a carrot, and a few of the outside stalks of celery, cut into the soup with the tomatoes, improves it for most people. Strain through a fine colander or coarse sieve, rubbing through enough of the beans to thicken the soup, and send to table hot.

Because this is a midseason bean, requiring about 100 days from planting to harvest, the turtle bean will produce good crops in most parts of the United States. The original strain is a semirunner, producing a bush with a sprawling vine about a yard long. I recommend growing the bean on deer netting, trellising, or on 3-foot stakes so that the bean pods will not rest on the ground. This will prevent crop loss in the event of wet weather.

Cornell University recently developed the Midnight Black Turtle Soup Bean, introduced commercially by Johnny’s Select Seeds of Albion, Maine. This is an improved upright strain that does not sprawl. Market gardeners may prefer this for harvesting convenience, and I cannot detect any difference in flavor. But Midnight Black should not be confused with the original heirloom variety.

‘Trail of Tears’ Bean

Phaseolus vulgaris

Historical documentation of this bean is thus far lacking, but recent oral history is rich. The seed came to Seed Saver’s Exchange in 1985 from Dr. John Wyche, a dentist of Cherokee descent who lived in Hugo, Oklahoma. Dr. Wyche also owned the Cole Brothers Circus, which supplied him with elephant manure for his extensive vegetable gardens. He was fascinated with Cherokee foodways, and from his Cherokee connections obtained the bean now known as Trail of Tears (SSE BN-1485).

According to Cherokee tradition, the bean was carried from North Carolina to Oklahoma during the forced march of the Cherokee Nation during the winter of 1838–39. Several thousand Cherokees died en route; thus the bean has become a potent symbol of their struggle for survival and identity. Because of this association, the Trail of Tears Bean is doubtless one of the most haunting of all the vegetables in the garden.

The beans produce vines with rich olive-green leaves with brown veins. The plants reach about 8 feet tall and must be well supported—they will grow well on tall corn. The 6-inch pods ripen to a maroon brown that dries into horizontal bands of black and tan. The seed is jet black, oblong, and very shiny. The young pods are used as snap beans, but the original use of the bean among Native Americans was for flour. It was also cooked in combination with blue and black corns. The Indians often added ash of certain herbs to their stews instead of salt. This alkaline action released the vitamin B in the corn and turned black beans blue. A little baking soda will cause a similar reaction.

Lima Beans

Lima beans are among the oldest documented New World vegetables, traceable back to at least 5,000 B.C. in Peru. According to reports from Spaniards who first occupied Peru, lima beans were only eaten by the Incas and other Indian elite. The rest of society consumed common beans. Small-seeded varieties of the lima were also known in Mexico during pre-Columbian times, yet there is not much evidence that lima beans had spread northward to American Indians beyond the Southwest until introduced by European settlers. Mottled forms are known to have grown in Florida around old Indian sites, but may have been introduced through early contact with the Spanish. The Spanish and Portuguese were largely responsible for disseminating the lima bean to other parts of the world. Our English word for it, which refers to the Peruvian capital of Lima, more or less confirms the South American origin of the seed first studied by European botanists. Some of the old German herbals called it Mondbohne or “moon bean” in reference to the quarter-moon shape of the seed pod. The moon still figures in the species name lunatus, “moon-shaped.”

Once, while visiting friends in Germany, I was invited to prepare an American dinner. I wanted lima beans, but they were nowhere to be found. Then, quite by accident, I discovered them, but the package was labeled in Chinese. In Germany, lima beans are exotics found only at American military bases or in Chinese grocery stores. This is an odd twist for a vegetable as American as apple pie, but the truth is, the lima bean has not found favor in European cookery. Due to Europe’s northern latitude, limas do not often produce flowers in regions north of the Alps. The heavy European soils that bring forth cabbages in abundance will yield to the fava bean but not to the lima.

However, Georg von Martens recognized the importance of the lima outside of Europe, and in the second edition of his classic book on beans (1869), he added a section on limas that is both brief and curious, for it is based mostly on the study of the seed. Remember, this was a botanist who could only grow limas in flowerpots, and his conclusions were tempered by this somewhat awkward mode of inquiry. The image of von Martens hovering over his seedlings is certain to make an American gardener smile, considering that the Carolina Lima can erupt into a vine well over 16 feet long. It was this huge vine size that discouraged many people from raising limas in the first place. Yet Meehan’s Monthly (1892, 12) recommended limas for this very reason, noting that for market gardeners, the bean was always profitable because the difficulty of getting poles meant that it was not as widely grown in home gardens as it could be.

Henderson’s Bush Lima, introduced in 1889, eventually changed this. As The American Garden (1889, 124) pointed out, “for many years we have worked hard, and doubtless many others did, to secure a new type of an inimitable lima bean which would not need the costly and unsightly poles, but without success, when suddenly from the Virginia mountains it is heard that plain farmers have had such a thing for years and said nothing about it.” Like many heirloom vegetables today, the bush lima rose from obscurity after years of cultivation in one locality. The only complaint against Henderson’s introduction was the smallness of the bean.

Limas are categorized into horticultural types, and one determining characteristic is the seed. The small-seeded limas are often referred to as sieva limas. They are annuals and are classified by botanists as Phaseolus lunatus var. lunonnus. The large-seeded limas are perennials and sometimes classified as Phaseolus lunatus var. limenanus or Phaseolus limensis var. limenanus. The obvious inadequacy of this taxonomy reflects the very unsettled nature of science in its attempt to organize beans in a logical manner. It becomes a nightmare when these limas are crossed and recrossed to produce new varieties. All types of limas will cross readily, even though limas are self-pollinating. Because they contain rich nectar, lima bean flowers are very attractive to bees. Therefore, two varieties of lima bean should not be grown in proximity unless they are caged or bagged, rather inconvenient for the large vining types in any case.

Seed saving is not complicated. Lima bean seeds are harvested from pods dried on the vine. Many of the truly old varieties like Carolina Lima have small pods that actually pop open when touched or when jostled by the wind. This is a characteristic of the truly old, primitive limas as well as of the wild ancestors of the limas we cultivate today. The dry seed pods are also woody and sharply pointed; thus, it is better to wear gloves when harvesting dry seed. Seed of most limas remains viable for three years.

For culinary purposes, limas can be harvested young and eaten fresh or ripened and dried for winter use. Dried young limas were popular in the past, and the technique for drying them is quite similar to that used by the French for flageolets verts. The Pennsylvania Farm Journal (1853, 197) recommended drying the beans in an airy loft: “Pull and shell the beans a little younger than they are usually gathered for use in the summer season. Spread them thinly upon the floor of a garret or an airy loft, and occasionally turn them until they are dry. Soak them twelve hours before cooking, in warm water, and when cooked they will be as tender, plump, and good as at any season of the year.” My great-grandmother dried her limas that way, having first spread the attic floor with newspapers. Lima beans dried green reconstitute themselves and are far more tender than the beans ripened on the vine. Most of the old varieties listed here are excellent when dried this way.

There are hundreds of heirloom limas available to gardeners today, some varieties very similar to one another, some so unusual that they are only grown as curiosities — I think the Brazilian black-seeded limas fall into this last category. For the sake of variety, I have included several with unusual colors, but still useful as culinary beans. My favorite is Dr. Martin’s, and I still maintain plants descended from seed my grandfather bought from Dr. Martin when he was selling the limas for 25 cents apiece.

‘Carolina’ Lima Bean

Phaseolus lunatus var. lunonnus

This 80-day variety is known to date from pre-Columbian times. It was depicted by Matthias de l’Obel in 1591 and is thought to be the “bushel bean” known in the Carolinas as early as 1700. There are claims that this bean is indigenous, but more likely it was introduced from Jamaica. Thomas Jefferson grew this variety at Monticello in 1794, and visitors can see the beans rambling over their tall poles even to this day. The popularity of the Carolina Lima in the South gave rise to a great many synonyms, among them Carolina Sewee, Saba, Sivy, and West Indian. This bean has the advantage of being one of the earliest of all the limas, and for a dry bean it is prolific, best suited for drying green. As a shelly bean it is not as desirable, although it was used as such in colonial times.

The vines are vigorous, reaching 10 to 12 feet in length, in good ground even as long as 16 feet. Each vine produces many small pods about 3 inches long as snown in the drawing. The pods normally contain 3 chalky white seeds, very small and flat.

‘Hopi’ Lima Bean

Phaseolus lunatus var. lunonnus

This is not a true garden variety in the sense of Dr. Martin’s or the Carolina Lima; rather, it is a strain of lima preserved among the Hopi peoples, which exhibits characteristics of crossing. The bean is used primarily as a dry bean among the Hopi, who also sometimes grind it for flour. Pure seed is small, the same size as the Carolina Lima, orange in color, with maroon-red markings. Nicholas Joseph de Jacquin (1727–1817) obtained samples of a lima bean similar to this sort from the island of Bourbon in the Indian Ocean during the eighteenth century. However, there is reason to believe that it originated in South America, the product of a cross between a solid maroon red sort and a plain orange-seeded variety, for it comes very close in appearance to an orange sort with dark markings found in pre-Columbian graves in Peru.

The age of the Hopi lima is not known, but if it existed for any length of time in the Southwest, it was most certainly plain orange in its original form, because it is not completely fixed as a variety.

Even today, it produces both plain and speckled seed. Georg von Martens (1869, 96) discussed the plain orange sort that was introduced from Brazil into West Africa during the 1600s. I obtained plain orange seed from Cameroon in 1993 and found it to be identical to Hopi lima in most ways, colored markings aside. When crossed with the Red Lima, it yields seed with the distinctive maroon-red markings.

Visually, the seed of Hopi lima is quite attractive, and since the vines are short, 6 to 8 feet long, and very productive, this is an easy variety to grow, producing crops in about 75 to 80 days. Since it is a desert variety, or at least a tropical one, it is resistant to heat and drought. For seed-saving purposes select only the seed with the finest markings; otherwise the variety will deteriorate into a plain orange-seeded sort and a purple-red one.

‘King of the Garden’ Lima Bean

Phaseolus limensis var. limenanus

This old standby was developed by Frank S. Platt of New Haven, Connecticut, in 1883, but not made known commercially until 1885, when an article describing it appeared in the Farm Journal (1885, 27). The original picture from that article is shown. The advantage of this variety is that it was developed in lower New England and is therefore better suited to northern gardens than many of the old varieties like Carolina Lima, or even more recent ones like Dr. Martin’s.

The vines range in length from 6 to 9 feet and are productive over a long period of time. The pods measure 5 to 8 inches in length and contain 5 to 6 seeds per pod. Vines come to crop in about 90 days. The seeds are large, usually dull white tinged with green when dry, and covered with small wrinkles. The shelly bean is said to taste like honey, but I think it tastes more like fenugreek. As a flavor combination, this bean goes well with curries.

‘Red’ Lima Bean

Phaseolus lunatus var. lunonnus

This heirloom variety was introduced commercially in 1990 by Southern Exposure Seed Exchange under the name Worcester Indian Red Pole Lima. It is said to be of Native American origin, but it conforms in many ways to the old red limas known since colonial times in several parts of North and South America. In fact, Georg von Martens obtained samples of this lima from Indonesia in 1868. Von Jacquin recorded it even earlier in 1770. In this country, the red limas were never considered of commercial importance and thus were grown more as a poverty food than as a preferred sort.

The shelly bean is uninteresting and tough, but the dry bean, which is deep maroon red, is both handsome and excellent cooked with red corn or ground for flour, two uses for which it was valued by the American Indians. In the South slaves cooked this bean with brown goober peas and mixed the bean paste with with red sweet potatoes to make fufu dumplings. The bean was noted in Country Gentleman (1864, 47), but no mention was made about its hardiness. In fact, it is one of the hardiest of all the limas discussed here. It normally yields 2 seeds per pod and produces consistently over the summer. The seeds and pods are the same size as the Hopi Lima and burst open when dry in the fall.

‘Speckled’ Lima Bean

Phaseolus lunatus var. lunonnus

There are a number of speckled or mottled heirloom limas, very similar in shape of seed and coloration, but widely different in pod and vine type. The best known of these is the Florida Butter or Speckled Pole Lima, an old variety of unknown origin but thought to descend from the speckled sorts once cultivated by the Indians in that section of the country. The author of Beans of New York (Hedrick 1931, 87) speculated that this variety evolved out of a speckled sieva-type bean, and this is quite possibly so. Boston seedsman John Russell listed a Speckled Saba Lima in his 1828 seed catalog, certainly one of the earliest references to this type. Massachusetts seedsman James J. H. Gregory listed a speckled lima bean in his 1864 catalog, and this like Russell’s appears to be the same as the Mottled Sieva described by Fearing Burr. The true Speckled Lima or Mottled Sieva is identical to the Carolina Lima except for the mottled coloring on the seed. It is as old as the white-seeded Carolinas and may have been more widespread at one time. Early accounts refer to it growing up trees and virtually weighing them down with an abundance of pods.

There is also a dwarf mottled variety worth mentioning. It is called Simmons Red Streak Lima or John Harmon Lima, a Pennsylvania Dutch variety taken to West Virginia, where it was preserved. The vines are about 4 feet long, with most of the pods toward the bottom. The leaves of the plant are crinkled and waxy on the top, the flower color white. Like the speckled lima, this is a white bean splashed with maroon as though dipped in color. For gardeners concerned about space, this dwarf variety is excellent, and the shelly bean is not too bad either, although it must be picked very young.

‘Willow Leaf’ Lima Bean

Phaseolus lunatus var. lunonnus

This 100-day variety is believed to have been introduced in 1891 as a sport of the Carolina Lima by W. Atlee Burpee of Philadelphia, although Thomas Mawe mentioned a willow leaf sort in Every Man His Own Gardener (1779, 482). The name of this variety is derived from its leaf, which is shown in the drawing. I am not convinced that it resembles a willow leaf; to me it looks more like bamboo. It is because of this decorative leaf, however, that the bean is often grown as an ornamental. Otherwise, it resembles Carolina Lima, and like that variety, it is drought resistant and thrives in long, hot summers. It also requires large poles for support, since the vines reach anywhere from 8 to 10 feet or more (mine grew to 22 feet the first year!). The leaves and pods are a dark glossy green. The pods are 3 inches long and contain 3 smooth white seeds.

Runner Beans

Runner beans belong to the species coccineus and therefore will not cross with common garden beans or with lima beans. The Spaniards were the first to see runner beans in the New World and the first to introduce them into Europe. The French

name for runner bean, haricots d’Espagne, recognizes this path of introduction. However, in old German herbals, runner beans are often called Arabische Bohnen (Arab beans), since the first specimens came into German botanical collections by way of Turkey. Runner beans take their name from the fact that they are vigorous climbers, and unlike most beans, wrap themselves counter-clockwise around poles or stakes.

Runner beans are known to have been introduced into England in 1633 by John Tradescant, gardener to Charles I. Tradescant knew four sorts, a red-flowering variety, a bicolor (red and white), a white-flowering sort, and a black-seeded one. These early introductions have been equated with the varieties now known as Scarlet Runner, Painted Lady, White Dutch, and Black Coat respectively. Black Coat was mentioned specifically by German botanist Michael Titus in his Catalogues Plantarum (1654), so there is no doubt about the age of this variety. Its flowers are a distinctive orange-red.

The commonest culinary runner bean on the Continent was the white, in England the scarlet sorts. In this country the scarlet runner bean was normally raised as an ornamental, while the white sorts were used in cookery. For American gardeners lima beans supplanted the runner bean as a kitchen garden vegetable except in areas where limas were difficult to grow. Runner beans of all sorts are generally used as shelly beans, and when cooked in this manner, they resemble fresh limas. The pods toughen as they mature, but if harvested young, they can be used like snap beans. In fact, the Gardener’s Magazine (1830, 177) recommended shredding them and salting them down to make a type of sauerkraut. The old Pennsylvania Dutch method was to “whittle” the beans diagonally into long shreds called Schnipple, hence the Pennsylvania Dutch name for the bean kraut: Schnippelbuhne. The Germans did this with the white varieties and called the pickle Sauerbohnen. Whatever, it is much milder than sauerkraut and can even be served with fish.

Georg von Martens (1869, 82) devoted considerable space to the white runner bean because of its importance in European kitchen gardens. He collected samples from many regions and recorded their local names: haricot de Sainte Magdaleine in Algeria, judias blancas in Spain, fagiolo da brodo in Naples, and fasolone in Apulia, to name just a few. Sorting out the many existing varieties can be daunting, but for the heirloom gardener, the four sorts known to John Tradescant can be cultivated with certain reassurance that they were known in this country at least by the eighteenth century. Of course, it is presumed that runner beans were raised here in the seventeenth century, although documentation is lacking. It is true, however, that their culinary merits were not noticed in England until the 1750s, which would account for the lag of interest on this side of the Atlantic.

Nineteenth-century American cookbook author Eliza Leslie often mentioned the scarlet runner bean as a worthwhile vegetable, from which we may assume that it was probably not completely familiar to all her readers. She took care to explain how to cook the pods in her Directions for Cookery (1851, 197). Or should I say, overcook them?

Scarlet Beans Recipe

It is not generally known that the pod of the scarlet bean, if green and young, is extremely nice when cut into three or four pieces and boiled. They will require near two hours, and must be drained well, and mixed as before mentioned with butter and pepper. If gathered at the proper time when the seed is just perceptible, they are superior to any of the common beans.

Runner beans are not difficult to grow, but they do have certain peculiarities that can be considered advantageous on the one hand and inconvenient on the other. The beans are native to the highlands of Central America and therefore are not only day-length sensitive but, more important, prefer cool weather. If they are planted soon enough in the spring, the vines will begin flowering before the onset of summer, thus assuring a crop of seed. Long periods of hot weather cause the flowers to drop and not set pods; in many parts of the United States, flowering ceases in July and August. In areas of the country where summer evenings are cool, runner beans will bloom profusely throughout the season, just as they do in England.

In their native habitat, runner beans are perennial. They develop a thick tuberous root that can be lifted in the fall and stored like a dahlia. This feature was well understood by gardeners even in the 1600s, but literature on the technique is more recent. English horticulturist John Cuthill published an essay, “On Taking up the Roots of the Scarlet Runner in the Autumn,” in the Gardener’s Magazine 1834, 315, and his advice is still useful today. Lifting the roots, as shown in the drawing, has two advantages. Vines from tubers produce more abundant crops of beans than those raised annually from seed Furthermore, the tubers can be started in pots early in the spring, either in a cold frame or in a greenhouse, and thus the plants will have a head start when they are set out and flowering many weeks in advance of newly started vines. These points are particularly important where runner beans are being raised as a food crop.

For seed saving, keep in mind that runner beans have large flowers attractive to bees. Of all the beans in the garden, runner beans are mostly likely to cross if planted in proximity. I would recommend growing only one variety at a time, or at most two varieties widely separated and of entirely different seed color. Planting flowers nearby that are attractive to bees will help reduce the likelihood of crosses if there are other runner beans in the neighborhood. Seeds are gathered from the dry pods in the fall. Their viability is about three years.

‘Purple Hyacinth’ Bean

Dolichos lablab

I have included this under runner beans because it is treated like a runner bean when cultivated as a food crop. However, this bean is a different genus and species from all the other beans in this book and therefore will not cross with them. But it will cross with other lablab species. Unlike the runner bean, which is a New World plant, the hyacinth bean hails from tropical Asia and thrives on heat.

Visitors to Monticello are usually astounded by the grand display made by this bean when it is allowed to run over arbors the way Thomas Jefferson preferred to cultivate it. T

he purple flowers and seed pods are ornamental from any standpoint, and the dark purple leaves only add to its striking character. I have yet to learn why it is the Venetians call these beans moneghine, which means “little nuns” and seems ill-suited to the showiness of the plant. But perhaps it has to do with the seed, which is black and white. The young purple seed pods are edible and commonly consumed in Asia. In America, however, the bean is grown mostly as an ornamental.

Matthias de l’Obel illustrated a white variety of hyacinth bean in his Plantarum seu Stirpium (1591) under the name Phaseolus brasilianus, mistakenly interpreted as a runner bean even though the seed is clearly a Dolichos. Bernard M’Mahon sold the Purple Hyacinth Bean as early as 1802, but the plants were raised in the United States mostly by wealthy plant collectors like William Hamilton of Philadelphia and the scientifically curious like Thomas Jefferson. It is a telling comment on the popularity of the bean that it did not appear until 1824 in Edward’s Botanical Register (#830), and then only with a note that it was mostly raised from imported seed. This bean will not produce flowers in England unless raised in a greenhouse. I have found that of all the varieties of hyacinth bean now available, only the purple one of this sketch does best in my part of the country. The white-flowering, green-podded variety available from some seed houses does not bloom in Pennsylvania, and I do not recommend it to gardeners outside California or the subtropical parts of the country. Its growing season is simply too long.

Hyacinth beans may be cultivated like runner beans because they too require trellising or a fence to grow on. Hyacinth beans are also perennial, but short-lived. Therefore, they cannot be dug up and overwintered in the same manner. Saving seed is the best method of propagation. The secret is to start the plants early in large flowerpots, get them well on their way, then set them out when the weather is warm enough to plant tomatoes. Seeds are saved from the dry pods in the fall. Seed viability appears to be about three years.

Warning: The dry seeds of the Hyacinth Bean contains cyanogenic glucosides in toxic amounts. Asians treat the beans to remove the toxins, but for safety’s sake, I would recommend not eating the dry beans unless you are perfectly familiar with the cooking process. Be absolutely certain that the seeds do not fall into the hands of small children who might swallow them. The toxins work much more powerfully on children than on adults.

Read more: Uncover the history of heirloom bean varieties in Heirloom Spotlight: The History of Beans, and get more expert gardening advice on growing bean varieties in Grow These Heirloom Bean Varieties.

Find seeds for these heirlooms and more with our Custom Seed and Plant Finder.

Buy the brand new e-book of Weaver’s gardening classic in the MOTHER EARTH NEWS store: Heirloom Vegetable Gardening.

Photos and Illustrations Courtesy William Woys Weaver.